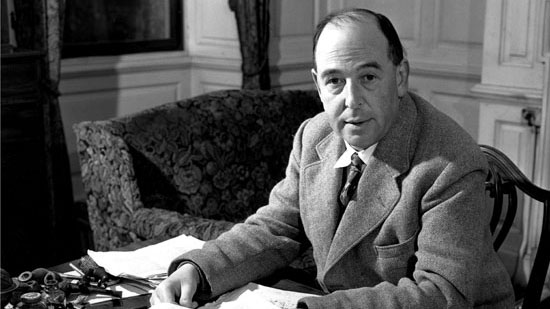

C.S. Lewis on the Dangers of National Repentance

In 1940 C.S. Lewis wrote an essay titled The Dangers of National Repentance in which he describes how young Christians in England had begun to decry their country’s role in World War Ⅱ. Although none of them had a role in the foreign policy that they took issue with, they nonetheless were prepared to admit their share in the guilt of England. Many of them started apologizing for the misdoings of their country—to which Lewis asks “Are they, perhaps, repenting what they have in no sense done?”

This concept—what Lewis calls national repentance—bears an uncanny resemblance to what is currently going on in America. Amidst the recent racial reckoning, many white Americans have found their consciences awoken to the injustices of the past and have begun to apologize for the actions of their race or country. Despite being far removed from the wrongdoings that they denounce, everyone from pastors to professors have taken to repenting as if the injustices were their own.

At first glance, the idea of corporate repentance—where an individual apologizes for sins committed by members of a group to which he or she belongs—seems rather harmless, if not noble. “Men so often fail to repent their real sins that the occasional repentance of an imaginary sin might appear almost desirable.”

But Lewis continues, “what actually happens (I have watched it happening) to the youthful national penitent is a little more complicated than that.”

He first notes how their behavior had a tendency to turn the Christian ethic upside down. Christians, he says, are called to be ruthless and punitive towards their own sins but gracious and charitable with the sins of others. Those engaging in corporate repentance are doing quite the opposite.

“When we speak of England’s actions we mean the actions of the British Government. The young man who is called upon to repent of England’s foreign policy is really being called upon to repent the acts of his neighbor; for a Foreign Secretary or a Cabinet Minister is certainly a neighbor. And repentance presupposes condemnation. The first and fatal charm of national repentance is, therefore, the encouragement it gives us to turn from the bitter task of repenting our own sins to the congenial one of bewailing – but, first, of denouncing – the conduct of others.”

Genuine personal repentance is a rather difficult task, but national or racial repentance costs nothing. It is, in reality, a bit of moral posturing—an “inexpensive virtue,” as he calls it.

How does this happen? Lewis continues:

“By a dangerous figure of speech, he calls the Government not ‘they’ but ‘we’. And since, as penitents, we are not encouraged to be charitable to our own sins, nor to give ourselves the benefit of any doubt, a Government which is called ‘we’ is ipso facto placed beyond the sphere of charity or even of justice. You can say anything you please about it. You can indulge in the popular vice of detraction without restraint, and yet feel all the time that you are practicing contrition. A group of such young penitents will say, ‘Let us repent our national sins’; what they mean is, ‘Let us attribute to our neighbour (even our Christian neighbour) in the Cabinet, whenever we disagree with him, every abominable motive that Satan can suggest to our fancy.’”

This phenomenon should be familiar to anyone who has been paying attention to the news in the last year. Many Americans—specifically white Americans—have begun to say “we” when speaking about injustices of the past committed by the government or by other white people. What they actually mean is “they,” but by lumping themselves in with the group they wish to condemn, they’re able to give the appearance of noble self-criticism.

This, as Lewis points out, is moral cowardice masquerading as virtue.

A slightly subtler version of this cowardice is the ritualistic disavowal of one’s “white privilege.” It takes the exact same form—repent of something you bear no guilt for in order to achieve a moral high ground from which you can condemn others who don’t fall in line.

While these kinds of behaviors are often done in an appeal to “justice,” Lewis helps us see that they’re simply counterproductive. Not only do they enshrine the color of one’s skin as a morally significant attribute (and thus work towards a more racialized society), but they do absolutely nothing to help those in need or bring real justice to those who have been wronged while simultaneously distracting from dealing with our own shortcomings.

We should be committed to repenting of our wrongdoings. And we should be committed to righting wrongs. But we should stop pretending that racial innocence can only be achieved through bearing guilt for crimes we have not committed. We can (and should) advocate for justice without engaging in such absurdities.

As I have written elsewhere, our culture’s ability to be fooled into participating in unhelpful and unethical ideas operating under the guise of “compassion” or “justice” is second to none. But C.S. Lewis offers us a way out. Not only through his helpful correction to the notion of national repentance but through his example of how we must approach all cultural developments. Notice how he did not fall for the semantic games that were being played and did not blindly accept the conventional wisdom of his day simply because it was being marketed as virtuous. Instead, he thought deeply about the situation, used logic and reason, and proceeded to thoughtfully and consistently apply Christian principles to the circumstances before him. We would be wise to follow his example.